AS AN ESSENTIA L part of our retreat, we, Totus Tuus Journeyers, watched a movie after dinner, having absorbed the necessary preparations for tomorrow’s consecration and settled comfortably in the viewing room of the Montfortian seminary.

L part of our retreat, we, Totus Tuus Journeyers, watched a movie after dinner, having absorbed the necessary preparations for tomorrow’s consecration and settled comfortably in the viewing room of the Montfortian seminary.

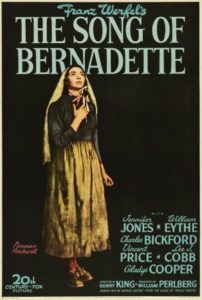

In the book’s foreword, American author George Weigel said of Franz Werfel’s novel, “On rereading the Song, what struck me most about Werfel’s craft was how deeply this Jewish writer, who had long been interested in Catholicism, but who had never converted, had entered into Catholicism’s sacramental imagination. For all its unsparing depiction of the poverty of the French Pyrenees, the pettiness of local officialdom, the skepticism and institutional-mindedness of local churchmen, “Song of Bernadette” is shot through with a sense of the extraordinary that lies on the far side of the ordinary, revealing itself through the simplest things.”

Wikipedia has this to say, “This is the classic work that tells the true story surrounding the miraculous visions of St. Bernadette Soubirous at Lourdes, France in 1858. Werfel, a highly respected anti-Nazi writer from Vienna, became a Jewish refugee who barely escaped death in 1940 and wrote this moving story to fulfill a promise he made to God. While hiding in the little village of Lourdes, Werfel felt the Nazi noose tightening and, realizing that he and his wife might well be caught and executed, made a promise to God to write about the “song of Bernadette” that he had been inspired by during his clandestine stay in Lourdes. Though Werfel was Jewish, he was so deeply impressed by both Bernadette and the happenings at Lourdes, that his writing has a profo und sense of Catholic understanding.”

The 1943 film, graciously shared by repeating fellow journeyer Sis Baby, was in black in white, too grainy to gain appreciation from even a film buff, and its sound left a lot to be desired. We sat through it until midnight and saw that some of our pilgrim companions could not hold their yawns longer than the movie. I had to do some research to make sure my strained understanding of its talkie does not rob the movie of the grace that guided me throughout its screening.

Bernadette was one of four children of a dirt-poor Francois, a miller, and Louise, a washer woman. They had only two cots, one shared by the parents and the other by the two daughters, so the younger boys slept on the floor.

Her out-of-work father was advised by the baker that there was only room for one in the latter’s bakery and to try looking for work at the hospital, where he was easily accepted as the garbage man, collecting trash and emptying it at the dumpsite.

In school, Bernadette was simple-minded and slow, because sickly. When asked by the nun who the Holy Trinity is, she could not answer for, defended her sister Marie, she was stricken with asthma when that was taught. The visiting Fr. Peyramale gave pictures of the Holy Family to selected students that day but the teacher recalled Bernadette’s share and gave it back to the priest.

Arriving from school, Marie was told by her mother to fetch firewood for the fireplace. Bernadette wanted to go with her (and their friend Jeanne) and Louise, even if against her catching cold easily, was prevailed upon.

Slow Bernadette could not catch up with her energetic companions and was hesitant to cross the bridge by the house of Antoine and his mother. Antoine sensed her reluctance and helped out. The girls had to cross a shallow river to get to where firewood was. The place was near the dumpsite. Marie warned Bernadette that the water was freezing cold so she stayed behind. Alone and with nothing to do, Bernadette walked towards the cave below the dumpsite. A lady in white, with blue girdle and a golden rose on each foot, appeared to her on a recess by the cave. When the two girls returned, Marie could not stop euphoric Bernadette from wading in the river that was, according to the latter, lukewarm as dishwater. She was acting strangely Marie had to ask why. Bernadette made them swear first before telling.

Back home, before Bernadette could warn Marie, the latter has told their mother about how Bernadette ran all the way from Massabiele excitedly because of the lady. This got the mother started on a scolding fit, the father joined in, and then thankfully a couple came bearing food and wine in thanksgiving for Louise’s saving the couple’s baby. A man arrived bearing news of a job for Francois who immediately announced the bounty must be shared by all. He said, “You brought eggs, we’ll have omelette.” The innate generosity – and prevailed-upon acceptance – of the poor.

In the second apparition, the lady told Bernadette that she has to complete 15 visits (the record counted 18) to Massabiele and that “I cannot promise to make you happy in this world, only in the next.”

Franz Werfel is the author of The Song of Bernadette (1941), a novel about the life and visions of the French Catholic saint Bernadette Soubirous, which was made into a Hollywood film of the same name.

She defied her mother’s admonition against going back to the dumpsite and being the laughingstock of Lourdes. Her Aunt Bernarde defended her by saying the dumpsite is no different from the stable where Jesus was born.

The city officials were getting alarmed and sought Dr. Douzou for his opinion of the “visionary.”

The doctor’ plain and professional examination of Bernadette resulted in the word “sinner” coming out of her mouth. He asked her what it meant and her reply was “one who loves evil.” He didn’t think her feeble-minded.

The city officials went to the Dean of the Church, who called the commotion “heathen gymnastics” yet, when asked how the dumpsite piety could be stemmed, sagely responded, “Prayer is good wherever it is offered.”

The Imperial Prosecutor and the Police Commissioner stepped in and ganged up on her to no avail. They threatened her father instead, whose fear of the law Bernadette could not disrespect. She suffered. Her parents could not bear their daughter’s misery and so went with her to Massabiele.

In her audience with the skeptical Dean of Lourdes, the priest dared her to tell the lady to perform a little miracle: make the wild rose bloom outside its season. In all innocence and faith, Bernadette agreed. With her parents and the community, she went back to the niche, kissed the lady’s feet, and heeded her bidding to “go to the spring, drink of the water and wash there.” She was about to run to the river when the lady said, “No, not the river, the spring yonder, eat of the plant.” There was no spring among the bushes, which she readily ate, her mother aghast at the sight of her. The next natural thing Bernadette did was scratch and dig the ground and, believing it was a spring, washed herself with the soil, which was too much to bear for a loving mother. Because the general crowd was already laughing at her daughter. The police shooed everyone away from the stupid spectacle. All but Antoine and a blind, I-told-you-so heckler. Who used to be a stone cutter but was blinded by a piece of marble. And so blamed God while asking for a cure.

Despondent, because in sympathy with the girl he silently admired, Antoine asked him to be quiet and leave him alone when, rising on his right arm, he felt water. Streaming from the very ground which Bernadette scratched and dug. The miracle that was not what Fr. Peyremale asked for.

The stone cutter, no longer a blamer because suddenly a believer, washed his eyes in the water and from there went running to the optometrist. The eye doctor examined him through an eye chart, which the man could not read, because he never read all his life, but could see, like everything else around him.

While the miracle rumor spread, the people built a wall around the spring and made a grotto out of it. The same couple’s dying baby, its legs paralyzed, was being given extreme unction by a young priest. The mother could not stand it, grabbed the baby and, despite protestation from her husband, hastened to the spring, and immersed her baby in it. As soon as it hit water, the baby cried. Lustily. And, upon later examination, without paralysis. On his way out, the young priest exclaimed, “Last night, when I was here, it was very dark. It’s much lighter now.”

The father of the baby, whom Louise saved earlier, said to Francois, “We’ll have an omelette, 10 feet wide.”

In her second audience with the still doubtful Dean, Bernadette caught his attention when she described the lady as the Immaculate Conception. The feeble-minded girl may know the meaning of “immaculate” but “conception” confounded the priest and made him accuse her of “playing with fire.”

The miracle brought the sick and the afflicted into Lourdes, filled its hotels with pilgrims and the mayor with greed.

Another doctor, of higher authority, sarcastically asked Bernadette simple questions which she answered until a stupid one (what is the sum of 17 x 18) stumped her. Yet her naiveté retorted, “Would you know the answer if you haven’t figured it out before?”

Along with the other Thomases, Sr. Marie Therese is not only antagonistic towards her but also claims to be praying that Bernadette be spared of the danger the latter caused herself.

In spite of a commission convened to grill Bernadette in an obvious attempt to discredit her, she remained steadfast and unchanging, and the church dubious. The grilling hounded her dying days.

Bernadette was off to be a nursemaid in the Convent of the Sisters of Nevers. With nothing to convince him further, the Dean saw her off with the same holy picture and renamed “heavenly” the fire that he initially alleged she was playing with. Further ahead, Antoine awaited, with a fare-thee-well bouquet. No longer silent, he told her that he’ll never marry. Bernadette responded by breaking a stalk from the bunch to give back to him.

In an interview with the Mother Superior, Bernadette would meet Sr. Marie Therese again, who still disliked her and deemed she ought to be renamed Marie Bernarde. She continued to torment her because of her envy and pride even when Bernadette started to limp. She accused Bernadette of getting attention and many other condemnations and confronted her with why the lady chose her instead of a nun who has suffered all her life. She will believe, concluded the nun, if shown proof. Bernadette wanted so much to help the poor nun and finally found how. She showed Sr. Marie her large tumor in the knee. Coupled with bone tuberculosis that had plagued her for a long time, a doctor called her suffering too horrible to describe. This sent Sr. Marie running to the altar to pray for forgiveness and promise to serve Bernadette for the rest of her days. Such was her remorse she kept her word.

Told of a trip back to Lourdes, Bernadette’s sad response was, “Spring is not for me.”

Told of a trip back to Lourdes, Bernadette’s sad response was, “Spring is not for me.”

In her death bed, the Bishop read out loud to her the Commission Protocol, to which she repeatedly replied, “I did see her.”

The Dean received from her the holy picture. The stubborn Imperial Prosecutor, stricken with larynx cancer, returned to die and, to himself, asked Bernadette to pray for him before he did.

Fr. Peyramale visited her to say he believed in her. It was him who said the epilogue at the movie’s start, “For those who believe in God, no explanation is necessary. For those who do not believe in God, no explanation is possible.”

One last time, the lady appeared to her. She died happily.

From February 11, 1858 to his death in 1945, Franz Werfel believed and never stopped believing. I believe he was compelled to explain because of his need to couple faith with action, to merge words and deeds in sacred harmony, because a song like Bernadette’s will keep stirring the soul until it is shared.

In my heart of hearts, all throughout the film, I plumbed why Sis Baby shared her collection with us. She could not get over it. (I could not get over it even as I watched.) Unless she shared the ethereal experience. Like our communion with the moment haunted me and promised to preoccupy me until I reduce my reverie to a manifested memory. I pray that we are now one with the book’s author, its film adaptation, and the many people who were touched sufficiently – spiritually – by the song, to proclaim its heavenly fire.

Abraham de la Torre