ATE THELMA TEXTED me early Thursday morning that she won’t be able to join us at our weekly BEC meeting that night. Her husband’s first cousin died and they were going to the wake. Much as we missed her inspiring presence, we had to make do with the remaining five of our 8-member group, for Ate Liling and Kuya Al were also absent. It was my turn to facilitate that evening. Our gospel was about Christ’s parable of a judge and the widow. The judge feared neither God nor people. But the widow persistently went to him asking that he defend her rights against her adversary. So dogged was her determination that the judge, just to get her off his back, relented. The widow, having gotten justice, left him in peace. Christ’s counsel was to learn from the evil judge not because God does justice by him but that relentless cries for mercy move Him to answer.

ATE THELMA TEXTED me early Thursday morning that she won’t be able to join us at our weekly BEC meeting that night. Her husband’s first cousin died and they were going to the wake. Much as we missed her inspiring presence, we had to make do with the remaining five of our 8-member group, for Ate Liling and Kuya Al were also absent. It was my turn to facilitate that evening. Our gospel was about Christ’s parable of a judge and the widow. The judge feared neither God nor people. But the widow persistently went to him asking that he defend her rights against her adversary. So dogged was her determination that the judge, just to get her off his back, relented. The widow, having gotten justice, left him in peace. Christ’s counsel was to learn from the evil judge not because God does justice by him but that relentless cries for mercy move Him to answer. This strongly recalled a quote from Fr. Serafin Michalenko*, “Satan loves justice because, being sinners, we should be justly punished. He hates God’s mercy because with it, God forgives.“

Our sharing were as diverse as our personalities yet as interrelated to the Word. So deep were the reflections that, vividly in my mind, our word of life stuck: Pray unceasingly.

It would remain there for a while.

At the 8 AM Mass last Sunday, Fr. Ranie’s (see On Change, Feb. 22 issue) homily expounded on the same gospel. He introduced his (understandably) deep discourse with a light story. Of a lawyer and a doctor pursuing the same woman. And the lawyer, so enamored by the lady, was assigned to a weeklong legal conference so wanted to be sure that his rival will be held at bay. Before he left, therefore, he gave the woman seven apples, each one bearing the cautionary signage “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

Praying, he continued, is connected to our faith. Which should be as unceasing as the latter is steadfast. We should not lose hope if God delays His answer because of three things He wants of us: purify our motive, intensify our desire and appreciate His gifts more. He is never one to not forgive because He is mercy personified in Jesus. So “I-push mo yan,” he encouraged, “for along with your prayer’s progress will His mercy dawn.”

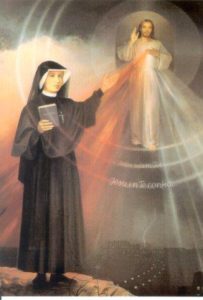

At that same Mass, I noticed early on that framed images of the Divine Mercy were festooned with flowers. And I asked myself whose nun-looking woman’s picture was that beside Jesus on the altar. I was to find the answer myself. For my reading time, I remembered a recent acquisition, a book given to me by fellow Totus Tuus Journey-er Sis Ana Marie, and picked it up. It was Face the Tempest by Manuel Martinez, about the life and spirituality of Sr. Faustina, the Saint of Divine Mercy. Later inquiry from Sis Rhea informed me that the day before, the Divine Mercy was enthroned.

Before opening a book, my habit is to read its blurb. I broke this and opened the yellow-covered curiosity at once. My reward was immediate. The author grabbed me with his opening comparison of orators Cicero and Demosthenes to musical masters Mozart and Beethoven. More so when he likened to thundering Beethoven uneducated, artless and simple Faustina Kowalska. I thought my life of prayer was substantial already. Sr. Faustina made me eat crow.

Martinez’ account was mainly culled from Sr. Faustina’s diary, Divine Mercy in My Soul, whose original was in Polish. Faustina did not like to write because, aside from finishing only Grade III, she claimed that words were too inadequate to describe the supernatural realities which she as a visionary experienced, especially her encounters with Jesus. But it was Jesus Himself who ordered her in an apparition to keep a diary of her experiences. The diary is the official English edition published by the Marians of Stockbridge, Massachussetts, USA, 2001.

The handwritten diary took a total of six notebooks. Jesus, in one of His apparitions, ordered her to write it. In spite of her difficulty and inability to write, because “how can a pen write down that for which there are no words,” since He gave the order, it was enough for her. As a printed book, the diary is now a magnum opus of 635 pages.

Sr. Faustina was canonized by Pope John Paul ll in April, 2000, the first saint of the millenium.

Besides being a visionary, Sr. Faustina was many things: peasant, self-flagellant, medieval, unattractive, prayerful, outdated, penitent, sickly, gardener, cook, bakery assistant, obedient, austere, self-denying, cheerful, friendly, submissive, giving, abstemious and nothing special. Topping all of these attributes was her total love for Jesus. If she were not a nun but a secular person, she would be deemed a clairvoyant or psychic. What she was, however, was a gifted mystic.

In her diary, she says that Jesus wants her to “fight like a knight.” And that set her apart from other spiritual athletes. For her diary is replete with grief, ecstacy, tribulations, consolations, pain, joy, but mostly love and Jesus’ divine mercy, the only ammunition she needed to dive to the depths of pain but rise to the heights of joy, beginning and ending each day in battle. Confessors, spiritual directors, convent superiors and guides helped her crystallize the Divine Mercy image, message and devotion, all upon the instructions of Jesus, that spread throughout Poland and the world. They include the Chaplet, 3 o’clock prayer and Novena.

The future nun was born in rural Central Poland on August 25, 1905. Baptized Helena, she was the third of ten children of a poor peasant couple. Her parents depended more on her in domestic chores because her two older sisters were already working as housemaids. Her parents were not formally educated but they could read and were very religious. They had a modest stock of religious reading materials which her father read to his children, the Bible among them.

Helena was marked for holiness. She prayed often as a kid, was compassionate to animals and, at the age of seven, had an experience of God calling her while she was adoring the Blesed Sacrament in church, one great necessity of her daily spiritual life. When she was already an adult, she could read the character, motives and the past of another person.

She sang religious songs, “Hidden Jesus” was her favorite, which is why, when she entered the religiious life, she adopted the name “Sr. Maria Faustina of the Blessed Sacrament.”

She started schooling at 12, got the highest marks in Religion but got only as far as Grade Ill for she had to work as a housemaid as well to help her parents financially. In school, as in the convent later, she was not popular with her peers because she was “eccentric,” poor and poorly dressed. Working away from home started her silent sufferings but most of the mothers of households she worked in described her as cheerful. This mindset and her strong love for God enabled her to survive loneliness.

The first time she asked for permission to enter the convent, her parents flatly refused. With their many children and poverty, they still needed her help. And help she did sacrificing her holy dream.

Working at various religious tertiaries later, her spiritual life deepened. Her self-imposed fasting came not from culture, custom or conviction but from a personal awareness of Jesus and His salvific suffering and her penance, be it heavy or light, from wanting to show her solidarity with Christ.

This spirituality was consolidated when the Virgin Mary appeared to her in a vision and told her, “Do not fear apparent obstacles but fix your gaze upon the Passion of my Son, and in this way you will be victorious.”

She again asked her parents’ permission to enter the convent, but again, they refused. She wrote in her diary that she turned over to the vain things of life, paying no attention to grace. She shunned God interiorly but her soul experienced deep torments. Then she saw Jesus, wracked in pain, all covered with wounds, who spoke, “How long shall I put up with you and how long will you keep putting me off?”

She went to church, fell prostrate before the Blessed Sacrament and begged the Lord what to do next. Then she heard the words, “Go to Warsaw. You will enter a convent there.”

Her incredible journey was made light because not only did she carry no material belongings but she also did not have any spiritual baggage to impede or delay her calling.

Her entry into the convent was not easy. Like everybody else in religious congregations, she had to pay for her wardrobe or some dowry. She could not afford it so worked for it – in gruelling loneliness and patience – as a servant for one full year. Probably because of the scar it left, when she became a nun, she wrote the rules for a proposed congregation making it a point that no qualified applicant would be refused immediate entrance for lack of money to pay for the dowry or wardrobe.

In her 13 years in the convent, she worked hard physically, mostly in lowly positions, but she did not mind at all. She would even spend her free time before the Blessed Sacrament. And she described an otherwise drab convent life as colorful, joyous and meaningful. Because lived in Jesus’ love and as an opportunity to do good.

Some nuns ridiculed and made fun of her. When she was sick, they would accuse her of feigning it or laziness to avoid work or spend more time in prayer, for everybody knew she was very prayerful. At times, she suffered from conspiracy and deliberate oppresion from others who took advantage of her goodness. She regarded their ill treatment, her sickliness and other pains as part of purification. Her entry in the diary read, “How can living surrounded by unfriendly hearts do me harm when I enjoy full happiness within my soul? How can having kind hearts around me help when I do not have God within me?” And on a Holy Thursday, she made a solemn Act of Oblation, a self-offering she had already been fulfilling daily, even when she was already wasting away in pain from disease, exhaustion and spiritual torments which included invisible stigmata.

In and out of hospitals because of health deteriorated by tuberculosis, she was sent to a sanatorium for confinement. Deprived of her daily Eucharist, she was devastated. But a seraph gave her holy communion for 13 days, one of her many encounters with angels. She wrote that there are nine levels of angels: Seraphims, Cherubims, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels. St. Michael was only immediately above the ordinary angel. Lucifer was a seraph and, without God, would have easily made mincemeat of Michael during their combat.

Two chapters in the book detail diary entries of her prayer, one of the things that distinguish humans from animals. But none can equal the perfect prayer of the Son to the Father. Sr. Faustina wrote that, “In whatever state a soul may be, it ought to pray. A soul which is pure and beautiful must pray, or it will lose its beauty. A soul striving after this beauty must pray, or it will never attain it.”

Because she was uneducated and owing to “folk Catholicism,” she was wrongly and wrongfully dismissed by the clever and sophisticated as fit only for the superstitious and unscholarly. She is downgraded because she wrote about so many apparitions and supernatural voices, perhaps more than any other well-known canonized writer. Her visions seemed like a disadvantage in that they rendered her suspect, that she was a fantasist, hysteric or pretender influenced by evil spirits.

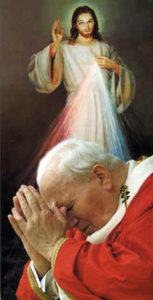

Then Cracow Archbishop Karol Cardinal Wojtyla, before he became Pope, was a student when Faustina died. He knew her story, was an expert on her, read her diary and was familiar with her Congregation of Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy, which was based in Cracow. In the 1960s, he asked an expert theologian, known for his sharp eye for dogmatic errors, to read the diary and subject it to the most withering scrutiny from the viewpoint of Catholic dogma. After reading it, the theologian told Wojtyla that the diary did not contain a single dogmatic error or departure from church doctrine. Instead of becoming Faustina’s critic, this theologian became an avid supporter of her beatification.

It was in Cracow where the Divine Mercy devotion started and spread out to the world. It was Pope John Paul II, a fellow Pole, who was convinced Faustina deserved canonization. But he took time and waited for the long official investigative process to take its slow, tedious course before beatifying her in 1993. He knew that both Fatima and Faustina were connected with the collective destiny of man, the former about events in the 20th century, the latter about the endtimes.

Interestingly, it was also Pope John Paul Il who used the words “How many roads must a man walk down before we can call him a man?” immediately providing the answer, “How many roads? Only one – Jesus!” after the singer-songwriter sang Blowing in the Wind in an open public audience with the Pontiff. Making it now clear why Bob Dylan was recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Interestingly, it was also Pope John Paul Il who used the words “How many roads must a man walk down before we can call him a man?” immediately providing the answer, “How many roads? Only one – Jesus!” after the singer-songwriter sang Blowing in the Wind in an open public audience with the Pontiff. Making it now clear why Bob Dylan was recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.In the chapter Encounters with Satan, a Fr. Corapi of EWTN offered this epithet: “Pride leads to disobedience, humility to obedience. Humility is the acknowledgment of the truth that God is Creator and we are only the humblest of creatures. But you cannot will to be humble. It is not in our nature to be humble. Humility is God’s gift. We must pray for it.” Doubtless, Faustina had humility in abundance. Satan’s powers were no match to her saintliness.

Her additional spirituality is covered in two more chapters all culled from her diary whose contents are mostly in prose, some in verse. Even if much of her poetry was lost in translation, it is said that the uneducated Faustina “hit the path of Polish poetry on her own without knowing literary patterns.” Her prose, clear, simple and forceful, was reflective of her character, sufferings and faith.

The book confirmed my reverence for priests, a mindset greatly influenced by fellow legionaries and BEC advocates. It posited – nay, proclaimed – that the greatest power on earth is granted to, and exercised by, priests when they are used as an instrument to turn the Host into the Body of Jesus. Even angels do not have this power, whose virtues are extolled when Sr. Faustina wrote that “If angels were capable of envy, they would envy us humans for two things. One is the receiving of Holy Communion and the other is suffering.” Would not we strive to bear a faint resemblance to that incapability.

From Fr. Ranie’s homily hammering, not intentionally, mercy that I always receive but often took for granted, to Sr. Faustina’s reverence and thanksgiving for her spiritual advisers, most of whom were priests, the weight of wisdom that rested on my head, beckoning me to reach for it, does not even start to approximate my humiliation for a belated realization.

I am heartened and humbled that, in my unworthiness, a gift as precious as a book on her life found its way into mine. One that hopes to aspire to at least be Bernadette’s broom to dust.

*in the book’s chapter Encounters with Satan (which the author returned to in the course of editing this piece)

Source: Face the Tempest, by Manuel F. Martinez, 251 pages, published by the Author himself

by ABRAHAM DE LA TORRE