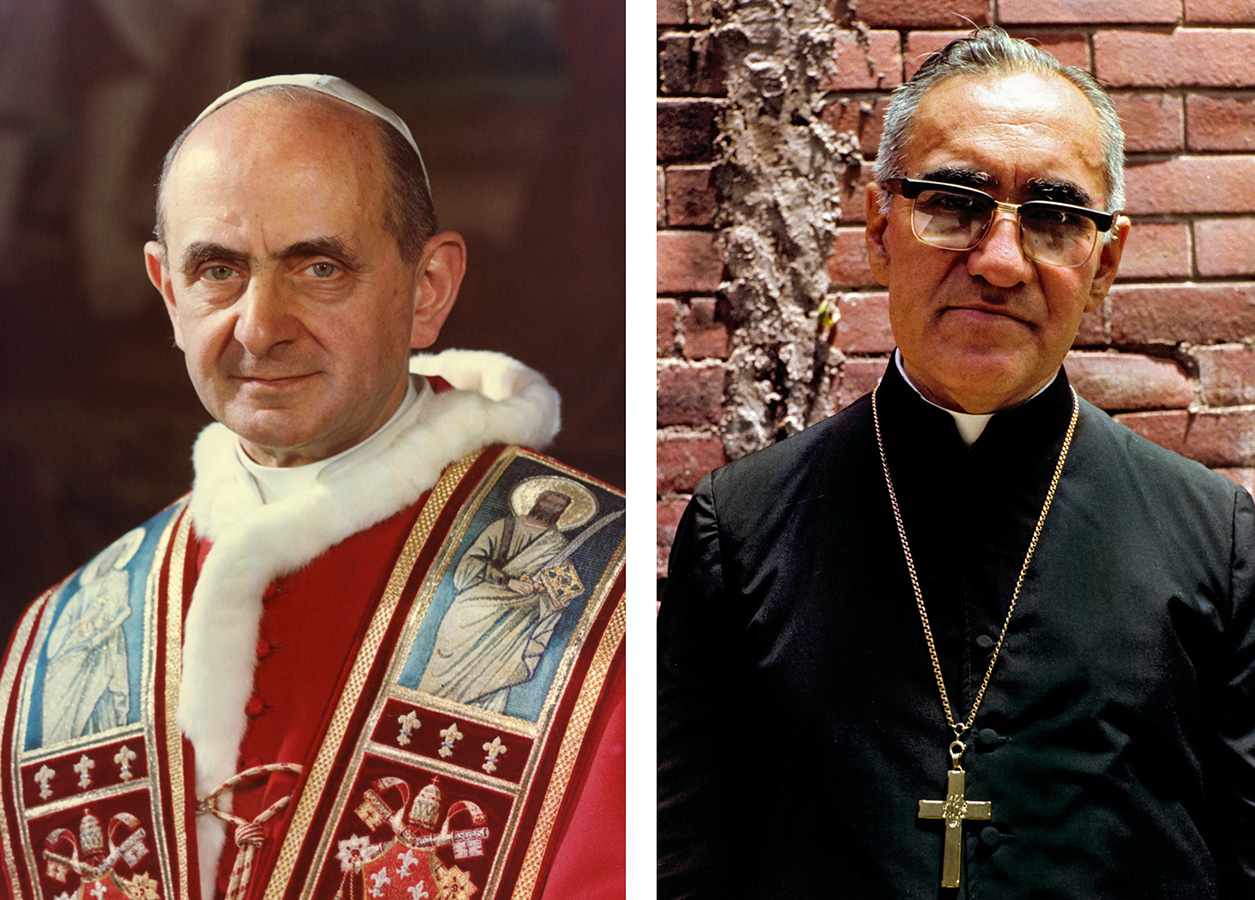

Beatification of Archbishop Oscar Romero a vindication for those working in conflict zones

by Inday Espina-Varona

As Catholics around the world celebrates the beatification of El Salvador Archbishop Oscar Romero as a “martyr of the faith,” embattled missionaries in the southern Philippines island of Basilan see the outpouring of support for Romero as a vindication of their mission to live amid communities in conflict.

The Claretian Missionaries, a community of Catholic priests and brothers founded by Saint Anthony Mary Claret in Spain in 1849, arrived in the Philippines some 50 years ago. It established strong roots in Basilan, an island-province that has seen some of the worst episodes of carnage in the half-century war for secession in the southern part of the country.

The Claretians’ mission varies depending on the needs of their area, but the missionaries mostly focus on “seeing life through the eyes of the poor” and respond to the biggest need at the time.

In the Philippines, the Claretians specialize in weaving back together the shattered lives of residents, immersing themselves in communities, and focusing on service rather than just evangelizing.

The beatification of Romero, a cleric killed by right-wing thugs for his support of the poor and oppressed of El Salvador, comes at a time when the Philippines is polarized by a proposed law that seeks to cement the peace agreement signed between the government and the country’s largest Muslim rebel group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

It has been a highly emotional debate, with some of the most vitriolic statements coming from people who have never lived in Mindanao’s conflict zones.

But the Claretian missionaries and the other survivors of kidnappings by the terror group Abu Sayyaf in Basilan say Filipinos cannot afford to give up on peace.

At the launch of the book Witness: Mission Stories of Basilan on Saturday, a teacher who survived more than a month of captivity in the mountains in 2000 explained why she returned home after 15 years.

[Witness: Mission Stories of Basilan is a collection of stories of missionaries who worked with the people of Basilan in the past 40 years. It is edited by Joe Torres, ucanews.com reporter and two-time Philippine National Book Award winner.]

Marizza Rante was a new teacher 15 years ago when the Abu Sayyaf attacked the Claret School of Tumahubong, taking hostage dozens of teachers and students, torturing and then killing Claretian priest Rhoel Gallardo. Three other teachers and five students died in the 2000 mass kidnapping.

The hostages emerged traumatized from the mountains of Sumisip town in Basilan. Many, fearing reprisals as they testified in criminal cases against the rebels and spoke of witnessing collusion by the armed forces, were brought to the national capital.

For years, the survivors, including Rante, tried to rebuild their lives, undertaking counseling to overcome the psychological cost of their ordeal.

But in 2013, Rante returned to Basilan to show her commitment to peace and set an example that young people, Muslims and Christians, and their parents can follow. She also said it was her way of honoring Fr Gallardo.

“I’m still here,” Rante said. “We have to move on,” she added. “I want to continue my work. I want to erase the bias against Muslims,” the teacher said, adding that there are only a few “bad” Muslims, some of whom are radicalized due to past trauma in their lives.

“The most tragic effect of war has been the suffering, the hatred and the division it has engendered in the hearts of so many families,” said Spanish Claretian missionary Angel Calvo, himself a witness to more than four decades of atrocities suffered by Muslim and Christian communities in Mindanao.

“Hundreds and hundreds of refugees pouring in from all corners of the island; schools and public places crammed with refugees not knowing what to do, where to go, or what to eat, day after day burying children who had died of hunger and neglect; and everywhere fear, panic, uncertainty,” Calvo writes in one of the stories that appeared in the book.

Calvo, a direct witness, sounds like what any priest who ministers to internal refugees would say today about the social and human cost of conflict.

“All those bodies bloodied, broken, decapitated. How many of them were there? No one will ever know. But there they will lie forever, their bodies germinating in silence and in suffering in the heart of this land,” the priest wrote.

Year in and year out, these scenes play out in the provinces of Basilan, Maguindanao, and other areas in Mindanao. Calvo said decades of war has wounded an entire people.

Greed and the vulnerability of communities to divide-and-rule tactics are the root causes of the Mindanao conflict, the priest said. But many of them choose to stay away from direct involvement in, for instance, debates over the proposed Bangsamoro Basic Law that would establish a new autonomous government for Muslims in Mindanao.

Calvo said laws are only part of the solution to a long-running conflict. There is no substitute to living with the people in troubled communities and showing them, in incremental ways, how they can together walk in peace.

That Rante and other victims of trauma are returning home, and Calvo and his colleagues are still living, amid the threats to their lives, is a testament of faith not so different from the martyrdom of Archbishop Romero of the Americas who was an inspiration to many Filipino activists, Christians and non-Christians, at the height of the struggle against the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines in the 1980s.

Inday Espina-Varona is editor and opinion writer for various publications in Manila.