by MSGR. FERNANDO G. GUTIERREZ

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee is a painting in 1633 by the Dutch Golden Age painter Rembrandt van Rijn, the only seascape ever painted by him. It shows Jesus calming the raging waves of the stormy sea, saving the lives of the fourteen men aboard the vessel. Of these fourteen men, Rembrandt included a self-portrait of himself in the boat next to Jesus and his four disciples.

The five men to Rembrandt’s right shout and strain at the sails, frantically trying to keep the ship from capsizing. The other four men to his left plead with Jesus to save them for they are perishing (SOS). Rembrandt stands in the middle of the boat, his right hand tightly holding on to a rope, and his left keeping his hat to his head. His name is faintly scrawled across the useless rudder, as though this is his boat on his sea, and they are all caught in this storm.

By including himself into the boat in the painting, Rembrandt conveys the message that the storm in one’s life makes no exemption (we are all in this boat together, he too goes through life’s turmoil). Life’s storm has no specific time. It can be at the beginning, middle and end of life’s earthly and spiritual journey); it has no definite duration (it can be a few days, months or years); it can be repetitious or occurs once in a lifetime.

Rembrandt wants us also to realize that there are a few options in the middle of crisis: either be lost in the darkness of the night and the tempestuous sea of abandonment or be saved by Jesus.

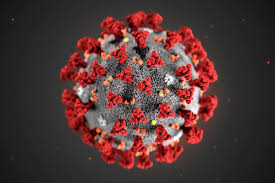

The whole world is under siege by the new storm: COVID-19, our unseen enemy. As a reaction, some shudder or cower in fear; displaced workers, vendors, tricycle and jeepney/bus drivers, indigent families, informal settlers and homeless people rely on local government units (LGUs) for food and financial assistance. Common responses are depression, sleepiness, moodiness, irritability and/or boredom due to the absence of physical exercise and high level of melatonin, the hormone that regulates the body clock. Quite a number of people suffer from cabin fever, the stress stay-at-home isolation or confinement in a place for an extended period of time. Such persons are described as stir-crazy (from the colloquial use of stir to mean ‘prison’).

For God’s sake, where is He?

Quite several Christians, Jews and Muslims ask, “Where is God in all of these critical and tragic events?”

Many utter, “Does God hear our pleas for mercy? Does he ever listen to our prayers? Is he concerned with what the whole word is going through?” This is the same question asked by Jesus as he agonized, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” But God did not respond!

Others begin to rethink their faith. They start to doubt about their belief in God. Some suffer in silence and still others do not care anymore or entirely gave up their religion.

Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor, wrote a play based on his book, Night. He described what he had witnessed during the Holocaust: a hanging of three victims. He was only 16 years old then:

[The head of the camp] had a young boy under him… a child with a refined and beautiful face…. One day when we came back from work, we saw three gallows rearing up in the assembly place…. SS all around us, machine guns trained: the traditional ceremony. Three victims in chains-and one of them, the little servant, the sad-eyed angel…. All eyes were on the child. He was lividly pale, almost calm, biting his lips…. The three victims mounted together onto the chairs. The three necks were placed at the same moment within the nooses…. “Where is God? Where is He?” someone behind me asked. At a sign from the head of the camp, the three chairs tipped over. Total silence throughout the camp. On the horizon, the sun was setting…. We were weeping…. Then the march past began. The two adults were no longer alive. Their tongues hung swollen, blue-tinged. But the third rope was still moving; being so light, the child was still alive…. For more than half an hour he stayed there, struggling between life and death, dying in slow agony before our eyes. And we had to look him full in the face. He was still alive when I passed in front of him. His tongue was still red, his eyes not yet glazed. Behind me, I heard the same man asking: ‘For God’s sake, where is God?’ And from within me, I heard a voice answer: ‘Where He is? This is where–-hanging here from these gallows…’

God’s “silence” is interpreted differently: Friedrich Nietzsche – God is dead; Martin Heidegger – absence of God; Martin Buber – eclipse of God. Karl Marx wrote, “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature as it is the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Atheists have their opportunity to conclude that there is no God. The atheistic view that “the dark night” is a form of masochistic propensity for pain due to a certain Catholic misinterpretation of suffering as spiritually redemptive. This explanation looks at suffering as a result of depressive states of mind and are not spiritual at all. This is the position of the atheist Christopher Hitchens. author of The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice and God Is Not Great: “She was no more exempt from the realization that religion is a human fabrication than any other person, and her faith could only have deepened the pit that she had dug for herself.”

Friedrich Nietzsche argued for the validity of atheism from his premise that God who the Jewish-Christian traditions claim as all-knowing and all-powerful, yet he hides from his creatures and does not help them understand his intentions. Such a God could not be one of goodness. Atheism contends that theism is logical if the believers are punished for their unbelief. But there are mystics, saints and devout believers, such as Mother Teresa, who had an experience of God’s absence, yet are punished. Goodness is a misnomer for him. Therefore, he concluded there is no God.

Christian view on God’s absence and presence

St. Thomas Aquinas said that God is greater than all we can say, greater than all that we can know; and not merely does he transcend our language and our knowledge, but he is beyond the comprehension of every mind whatsoever, even of angelic minds, and beyond the being of every substance. (Pseudo-Dionysius and the Metaphysics of Aquinas, p. 49)

St. Augustine said that God is incomprehensible. Thus, to think that someone comprehends him is to mistakenly comprehend something else for God. On the other hand, to think that someone almost comprehends, it is again because he allowed his own thoughts to deceive him. (St. Augustine. On the Trinity, XV, 19, 37)

Tertullian wrote:

That which is infinite is known only to itself. This it is which gives some notion of God, while yet beyond all our conceptions—our very incapacity of fully grasping Him affords us the idea of what He really is. He is presented to our minds in His transcendent greatness, as at once known and unknown. (Tertullian.Apologeticus, 17.)

G. K. Chesterton after the death of his wife wrote in Grief Observed, “The pain now is part of the happiness then. That’s the deal.”

Martin Luther who felt being left “alone in the universe,” doubted his own faith, his own mission, and the goodness of God. Doubts which verged on blasphemy and drove him deeper and deeper into desperation. His prayers met a wall of indifferent silence.

Later in life, he wrote, “God from behind; that is, we conclude that God has turned away from us, as he says in Isaiah (54:8): ‘For a moment I hid my face from you, but with everlasting love I will have compassion on you’; that is, ‘At first, I acted as though I did not know you, as though I had abandoned you.’ This is the view from behind, when we feel nothing but affliction and doubts; but later, when the trial has passed, it becomes clear that by the very fact that God has showed Himself to us from behind, He has showed us His face, that He did not forsake us but turned away His eyes just a little.

In the Christian tradition, there are two kinds of mystical experiences where on the one side of the spectrum lies kataphatic theology, and on the other is apopathy. The former is called the via positiva which reveals directly and makes ostensibly the divine beauty, while the apophatic, via negativa, dwells on divine glory that is kept from view and remains hidden.

Herein lies the mystery of God’s presence together with his hiddenness and remoteness that are often interpreted as the unfolding of himself while manifesting his absence and abandonment. It is called by Walter Cardinal Kasper as both revelatus (revealed) and absconditus (hidden).

Wholly Other and the One Who Is So Close to Us. His transcendence is not infinite distance and his nearness is not close chumminess. Our merciful God is not simply the saccharine “dear God,” who lets our negligence and malice pass. On the contrary, his salvific nearness is an expression of being different and an expression of his incomprehensible hiddenness (Isa 45:15). Precisely as the near and manifest Deus revelatus, he is the Deus absconditus. God’s mercy points us toward his Being Wholly Other and toward his complete incomprehensibility, which is simultaneously the incomprehensibility and reliability of his love and graciousness. (Kasper, Cardinal Walter. Mercy: The Essence of the Gospel and the Key to Christian Life. Paulist Press. Kindle Edition)

There is no light without darkness and no presence without absence. The pandemic, despite its harmful and deadly consequences, makes everyone to be more conscious of personal hygiene, social contact and family bonding. But above all, the COVID-19 global crisis makes the faithful to take seriously their faith in God which is normally for granted. The crisis has not only good physical, mental, emotional and hygienic results, but above it is transformative and salvific.

The meaning behind the story of Jesus calming the storm brings great encouragement and hope for anyone facing a storm in life. “You of little faith, why are you so afraid?” Then he got up and rebuked the winds and the waves, and it was completely calm. (Matthew 8:26) Jesus never leaves us, he is always by our side!

God’s hiddenness/revelation bring out the stark reality: as we journey through earthly life, all sufferings and challenges prepare us to eternal life where we stand face to face before God.