By: ABRAHAM DELA TORRE

MY FATHER PROSPERO died at 77. He was a retired government employee who rose from the ranks. His entry into government was as a security guard. Fresh from Albay and ill at ease with cityspeak, his speech was a smattering of Bicol, fractured Tagalog and good-enough English. In Bacacay, where I was born, credentials for teaching were not as stringent as the Civil Service Commission now strictly requires so he was easily hired to substitute an English teacher who was on leave. His English was a gift high school enhanced which he nurtured and took to calculated and confident heights, give or take a few, funny regional slips.

requires so he was easily hired to substitute an English teacher who was on leave. His English was a gift high school enhanced which he nurtured and took to calculated and confident heights, give or take a few, funny regional slips.

He compensated for his speech impediment by writing fiction. He contributed to the Philippines Free Press and Philippine Graphic every now and then. Which augmented his measly pay.

He was so adept at the language he was able to teach me how to read when I was five years old. Pepe and Pilar was his – and my – claim to literacy fame. When I was in Grade Two, one of my mother’s CWL friends heard me reading loudly and thought it would be a bright and unique idea if, in their coming monthly league charity bazaar, they had me as a guest speaker. An accidental social climber, whose seamstressing took her to the political swirl of church mesdames, Mama didn’t think twice about it and assigned my father the task of preparing a speech and its speaker for the event.

Being my very first foray into public speaking and an adult audience, I memorized the piece in no time at all. It never left my mind. And the idea of my father being a speechwriter and a speaker-maker concretized into fact.

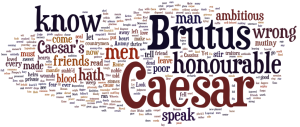

So much so that I swore he could do no wrong as far as English was concerned. He became my god. In high school, because of my being touted as an “Inglisero,” our English teacher entered me as a contender in the school’s oratorical contest, I was given “Break, Break, Break” to memorize. When I told my father about it, he asked me to recite the poem. He thought I was good but the poem was too short to showcase my skill. And gave me “Marc Anthony’s Eulogy” instead. I did not want to displease my god; I will worry about my teacher later.

Contest day. The first contestant delivered “O Captain, My Captain.” I was next. I did not have the butterflies when I delivered my very first speech at that CWL bazaar. They were nowhere when I went up on stage and rendered Marc Anthony. Then the third orator was called. He had the same speech as mine. A strange thing happ ened. He was speaking in a strange tongue. What I would learn later as a British accent. And he pronounced Caesar in British. And I remembered how I did it, in my father’s sorrily regional manner. The heretofore-unencountered name was foreign to my god and his complacency took it for granted. While I sweated marbles, butterflies swarmed in my belly. That was all I could recall of that woeful incident.

ened. He was speaking in a strange tongue. What I would learn later as a British accent. And he pronounced Caesar in British. And I remembered how I did it, in my father’s sorrily regional manner. The heretofore-unencountered name was foreign to my god and his complacency took it for granted. While I sweated marbles, butterflies swarmed in my belly. That was all I could recall of that woeful incident.

In class the next day, I was prepared for the worst. I understood my English teacher’s rage. That I took the liberty of changing my contest piece without a by-her-leave was unacceptable, she fumed. The worse part was that she kept mimicking my pronunciation of the C word – Caysar!

I did not begrudge my god that humiliating part of my high school life. On the contrary, I thanked my father for the lesson I learned from his mistake and my trusting too much he could do no wrong. From that experience, I became critical of speakers and words and no longer believed what I hear and read unless validated by a dictionary.

I owe my father my fascination with the English language. I owe him my penchant for reading aloud to myself, careful to enunciate every word, wary of his woebegone C word. I owe him my knack for writing because his unspoken legacy cautioned “Read, Read, Read to Write, Write, Write.”

In his memory, I reproduce hereunder, the speech he wrote for my nine-year-old oddity.

Distinguished audience of the Catholic Charities Association.

Since the time I was born, this is the only moment that I have been reluctant to talk, but I have been compelled to do so knowing that, so distinguished an audience as you and, so humble a person as I, may gain for me an experience that I may use, henceforth, in the propagation of the Catholic faith with the knowledge that God may see fit to give to me.

Even to my child’s mind, charity is such a beautiful subject. Those who are charitable are, indeed, children of God. They spread the gospel as much as those who pray and go to church do. Because the charitable give, they are generous and unselfish. And where generosity and unselfishnes thrive, there is a climate conducive for love to grow. There would be no room for intrigues. There would be no need for countries to wage war against one another. And we shall live in a world of peace. A world Jesus Christ gave His life in the cross for – to save. To save from what? From the sins of mankind. From greed. And avarice. And selfishness. And gluttony. A world He wanted to have more of charity. And love. And peace.

From my child’s point of view, your association, your conglomerating together to propagate charity for the religious’ great cause is a stepping stone to the preservation of peace for us. I hope and I pray, with all of you, that you succeed in your worthy endeavor. God bless us all. I thank you.