Father Alejandro Ochia Gobrin, CMF, Manila

Philippines

December 20, 2018

UCAN PHILIPPINES)

My congregation has the practice of sending missionaries who have been in the ministry for a considerable time to a kind of spirituality course, a going-back-to-the-roots updating process.

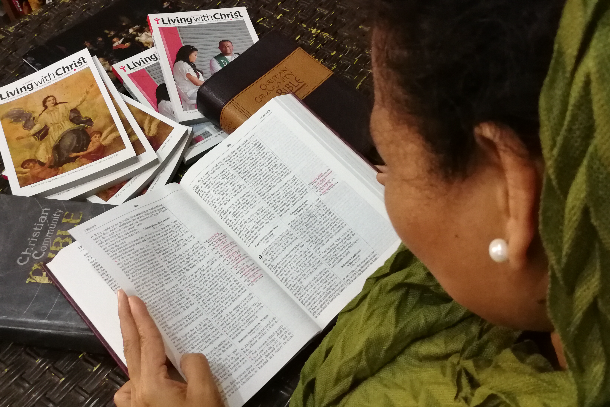

I was privileged to participate in 2014 in a such a group in Los Negrales, Madrid, where I encountered an article by the Italian Jesuit Carlo Martini entitled “My personal journey after Jesus.”

The article describes Martini’s journey of knowing Jesus from the Scriptures until he was confronted with the questions: “Are you willing to give faith to my words as words of God? Are you willing to recognize that my mission is the mission of the Father? Are you willing to trust me the ultimate consequences, like Peter who said: ‘You are the Christ, the Son of the living God?'”I saw a movement in Martini’s quest from text to the person of Jesus.

When I hear the words “text” and “interpretation,” I always remember the German philosopher H.G. Gadamer, who said that understanding the text is to reach a “fusion of horizons.”

But the questions of Martini remain. We have heard of the ideas of deconstruction, demythologization and the dismantling of the ancient Gospels in the search for the historical Jesus.

But we failed to paint a picture of Jesus because we lost the power and beauty of His narratives.As the Pontifical Biblical Commission insisted, we affirm that an “historico-critical” method takes a privileged place in the study of the Scriptures.

But what we encounter in the Sacred Texts is an imaginative, “theopoetic” language, symbolic and mythical.

What is important is not the factual description but the effective communication of meaning, thus, the historico-critical method may not be enough.

We need to engage in imaginative ways of interpretation.

The challenge we are facing today is not only the search for meaningful ways of engaging with the Bible.

We are also confronted with another equally important issue in our Biblical ministry: How to teach the Word?

I have been following American educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom’s ideas on learning, so I divided my teaching strategy to be (a) cognitive, (b) affective and (c) skills building.

I was fascinated by the idea of letting learners understand the text, love the text and learn how to touch and interpret the text with confidence.

But still I found it difficult to deeply penetrate learners with the Word.

I was looking for something more poetic, or maybe something dramatic.

When I came home from the missions in Colombia in February last year, I found my mother watching Ang Probinsyano, a Philippine television series involving police and gangster intrigues.

I was amazed that at 87 years old she was still religiously following the series.

Programs like this are very powerful, so I enquired why. The most common response I get is, “Because I can relate to it.”

“Relate” involves not only “fusion of meanings” but definite mental adherence, affective response, conviction valuation and applicative participation.

How do we engage with the Scriptures so that we can relate to them? Our text is not only a literary text but a faith text.

We may have to engage the Scriptures as narratives (stories) for us to be able to relate to them.

I call this way the “Narrative Way,” which is engaging the Scriptures as narratives of life happening today to people in the community.

Narratives are powerful. They create a world of their own. They can transform. They can dictate actions. It is interesting to note that even the business world exploits the power of narratives.

The Narrative Way seeks to engage the entire person or community in Biblical interpretation, which is like a young boy interpreting a song or a painter redoing the Starry Night of Vincent Van Goh.

The boy brings everything in him to give life to the music or the art.Biblical narratives are sacred because God is there. The real end game for Biblical studies is discovering God in the text.

Discovery happens when we are able to relate the text to our own narratives. Our own narratives are sacred because God is there. Evidently, we are our own narratives.

God is present in our narratives. If we can see God in our narratives, it is a lot easier to see God in our Sacred Texts.

Father Alejandro Ochia Gobrin, CMF, is Claretian Missionary and a professor of biblical studies and pedagogy in Manila.