Credit: Unsplash

.- Pope Francis’ remarks on the “wrong” translation of the Lord’s Prayer in a TV show hosted by the Italian Bishops’ Conference’s TV2000 network are part of a wider debate that has taken place in Italy for over two decades.

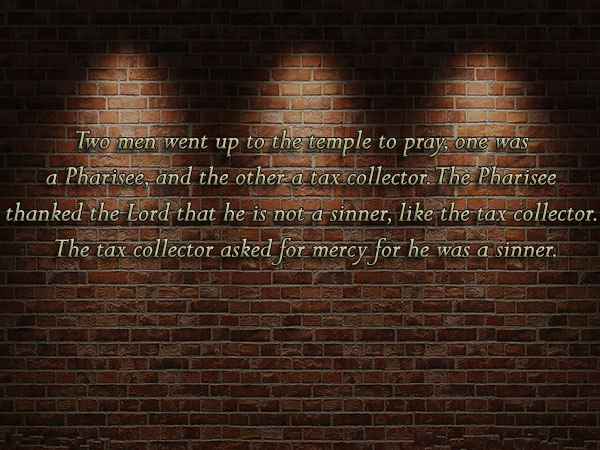

The Pope said that the words “non ci indurre in tentazione” – “Do not lead us into temptation,” in the English version – are not correct, because, he said, God does not actively lead us into temptation.

The Pope also praised a new translation operated by the French Bishops’ conference.

The new French translation is “et ne nous laisse pas entrer in tentationI” – “let us not enter into temptation.” It replaces the previous translation “ne nous soumets pas à la tentation” – “do not submit us to temptation.”

It is worth noting that St. Thomas Aquinas considered the question of whether God leads men “into temptation” in a commentary he wrote on the Our Father. The saint, and Doctor of the Church, concluded that “God is said to lead a person into evil by permitting him to the extent that, because of his many sins, He withdraws His grace from man, and as a result of this withdrawal man does fall into sin.”

The Pope’s intent seems to be to emphasize that God’s active will does not “tempt” men, that, instead, the permissive will of God allows people to be tempted because of their sinfulness. This is the emphasis of the French translation. The theological context is complex, but certainly the Pope has not intended to deny the theological and scriptural sense in which God allows, or permits, temptation.

However, the Pope was talking in Italian, on an Italian television show, and his remarks dealt with the Italian translation of the Lord’s Prayer. It would be a mistake to assign his remarks significance beyond the Italian context, in which they would be well understood.

And, in fact, a new Italian translation of that very sentence of the Lord’s Prayer has already been done.

The new translation of the Bible issued by the Italian Bishops Conference says “do not abandon us to the temptation,” and the rephrasing of that sentence was the fruit of a long process, aimed at being more faithful to the Latin text of the prayer – the so-called editio typica – and at the same time more fit to the current language.

Cardinal Giuseppe Betori, Archbishop of Florence and a well known scripture scholar, who has also served as undersecretary and secretary of the Italian Bishops Conference, recounted to the Italian newspaper Avvenire how the process for a new translation took place.

“The work,” he said, “dates back to 1988, when the decision was made to review the old 1971 translation of the Bible.”

At that time, a working group of 15 scripture scholars was established, coordinated by a bishop – the first was Bishop Giuseppe Costanzo, then Bishop Wilhelm Egger, and finally Bishop Franco Festorazzi.

This working group collected the opinions of 60 more experts on scripture. The group was overseen by the Bishops Commission for the Liturgy, and the Italian Bishops’ Conference Permanent Council, a group composed of the presidents of regional bishops conference, and the presidents of the commissions established within the Bishops’ Conference itself.

Cardinal Betori said that “within the Permanent Council, a restricted committee for the translation was established,” was composed of Cardinals Giacomo Biffi and Carlo Maria Martini, and of Archbishops Benigno Luigi Papa, Giovanni Saldarini and Andrea Magrassi.

“This committee,” Cardinal Betori said, “also received and considered the proposal for the new translation of the Our Father.”

The formula “do not abandon us to temptation” was adopted because it met the approval of both Cardinal Martini and Biffi, who “were not, as is known, from the same schools of thought,” Cardinal Betori explained.

Cardinal Betori said that the formula was chosen because it had a wider meaning, as “do not abandon us to temptation” can both mean “do not abandon us, so that we will not fall into temptation” and “do not abandon… when we are already facing temptation,” Cardinal Betori explained.

The new translation was approved by the Italian bishops in 2000. In 2001, the Congregation for Divine Worship issued Liturgiam Authenticam, a set of new provisions for the translation of liturgical texts.

After Liturgiam Authenticam, the whole work of translation was reviewed by a group of experts, led by bishops Adriano Caprioli, Luciano Monari and Mansueto Bianchi. Cardinal Betori was part of this group.

The revision, which suggested many amendments, was forwarded to the bishops. However, these amendments “did not change the proposal for the new translation of the Lord’s Prayer.”

The new translation of the Bible was finally approved during the 2002 General Assembly of the Italian Bishops Conference, with 202 out of 203 bishops voting favorably. The text of the Lord’s Prayer was approved separately, to be certain there were no doubts from bishops. The Holy See gave its recognitio in 2007, and the Italian Bishops Conference Bible was finally published in 2008 with the new translation.

The new translation of the Lord’s Prayer was ‘transferred’ to the Missal. However, the new translation, in order to be part of liturgical use, must be approved by the Holy See, and the text has not been approved, because there are other issues of concern in the Missal’s translation.

This is the reason why, the formula for the Lord’s Prayer in Italian is still “non ci indurre in tentazione.”

Ultimately, speaking about the translation of the Lord’s Prayer, Pope Francis did not say anything really new. Italian theologians and scripture scholars have already provided their solution for the translation.

However, there is another story to be told. There is a question regarding what will happen to translations that once needed a “recognitio” from the Holy See, which is now simply called to “confirm” the new translation.

Will this lead to a general change in translations in languages other than Italian?