By: Msgr. Fernando Gutierrez

Section Two

The Pre-Hispanic Years:

Formative Phase: Life of the Early Filipinos

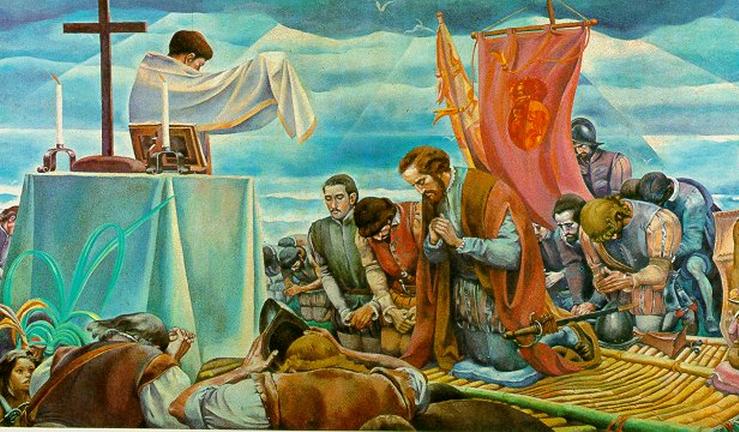

The pre-colonial spirituality of the Filipinos was animistic or polytheistic. They worshiped so many gods and spirits. These gods came to be associated with rivers, trees, and mountains. This experience, though erroneous, nonetheless showed the Filipino desire to capsulate the understanding of their gods. With the arrival of the sword and the cross, the spirituality and cultural values that were indigenous to the Philippines had changed. Though colonialism and Christianization had brought progress to the Filipinos, yet God’s image came to be foreign than Filipino and extensively associated with suffering and atonement. In some instances, superstitious beliefs and traces of polytheism continued to coexist with Christian faith.

Migration

Anthropologist F. Landa Jocano of the University of the Philippines believes that the early indigenous Filipinos were products of the long process of evolution and movement of people. According to him, the Philippines between the 1st and 14th Century AD was going through its “emergent phase.”

Popular belief holds that the majority of early Filipinos were agglomerations of migrants from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Asian mainland who came in diverse waves over many centuries and largely displaced the aboriginal Negritoes, the islands’ earliest inhabitants. As early as the 3rd century, various ethnic groups formed several communities in the archipelago: India, China, and southeastern Asia. They were formed by the assimilation of various native Philippine kingdoms.

National Identity

Before the Spaniards’ arrival to the islands, the Filipinos had already a way of life, a distinct culture, and forms of spiritual worship that were suitable and comfortable as far as the natives were concerned. They had a calendar, weights and measures, a system of writing, some elements of law, some religious ideas showing both Hindu/Buddhist and Mohammedan influences, and had some skill in metalworking, pottery making, and weaving.

Historians agree that pre-Spanish period Philippines was not yet a nation, with more than 7,000 dispersed islands, but each had its own history, ethnicity, regional dialects, and various religious beliefs. These differences were more evident through various autonomous kingdoms of Luzon Island, Mindanao Island, and many of the other islands. There was no unity as one archipelago under one dominant empire. However, the conquest by Spain and the introduction of Catholicism were the first steps in creating a national identity. Historians are divided whether or not the archipelago had its national identity by the time of the arrival of the Spaniards.

The whole region was divided and ruled by competing thalassocracies (sea-borne or maritime empires), such as the Kingdom of Maynila, Namayan, Dynasty of Tondo, Madya-as Confederacy, the Rajahnates of Butuan, the Visayas, and sultanates of Maguindanao, and Sulu.

Some of these indigenous groups were parts of other Asian kingdoms, such as the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit, and Brunei. These thalassocracies reveal the Hindu and Muslim influence on the early Filipinos.

Early Social and cultural progress

Before the Spaniards’ arrival in the Philippines, the archipelago was enjoying a relatively commercial growth by trading with other cultures.

“It was characterized by intensive trading, and saw the rise of definable social organization, and, among the more progressive communities, the rise of certain dominant cultural patterns.” (cf. Jocano.)

Indigenous Religions

The indigenous Filipinos not only manifested their progress in trade, commerce, and governance, but also revealed how they related to and conceived ideas about their gods and goddesses.

Long before the arrival of the Europeans, they experienced “supernatural” energy, an “encounter” with the divine. The rituals were intended not only to pacify evil spirits, but also to satisfy their need to celebrate that energy in many different areas of their lives and had gods and goddesses to participate in them. Thus, they had gods and goddesses for every time and season, in war, planting and harvesting, sickness, natural calamities, famine, and sex. Their spiritual life was related to every aspect of their daily living, even in the most mundane thing, such as cleaning the pigpen. there was a god or goddess to whom they could turn for any human need. The indigenous spiritual traditions are based on the belief that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad. They believed too that sometimes the gods were at war with each other. Their gods and goddesses often times interfered deeply with human lives, such as in earthquakes and storms.

Anitos were worshiped as saints because they were the soul of their pious ancestors. These ancestors were venerated for protection of homes and safeguard of families. Even today, certain Philippine regions offer food before a picture of the deceased. The idols were perfumed and dressed, comparatively in the same manner as the contemporary Christian saints are dressed.

The natives have many ritual practices that are opposed Christian faith. For instance, picking flower or fruit, they ask permission from the “Nuno” or tutelary spirit so as to avoid offending for trespassing. This is evident too when they pass through some field, river, brook, stream, or by a huge tree, permission is asked first. The “Nuno” is the origin of “Nuno sa Punso” or dwarfs, who reside at a mound of clay or bushes. To avoid displeasing the “Nuno sa Punso”, a passerby utters, “Please allow me to pass” (“Nakikiraan po”).