Section Three

Colonization Years: Deformation Phase

Deformation happens through times of peace and war. Those conflicts within and outside the geographical boundaries of the nation tested the Filipinos’ strength, made them gracious in victory, but magnanimous in defeat. Nonetheless, those times made them broken and wounded communally and personally, though they acquired certain benefits. However, they were beleaguered with fear and succumbed to the power that more than destroys rather than builds.

Spain’s Ulterior Motives

Apart from the intention to conquer or unify the scattered Philippine islands (a total of 7, 107), Spain had three other major goals for the Philippine archipelago. First, Spain intended to colonize and Christianize the entire archipelago. Second, Spain aimed to use the archipelago as port in its trade with China and Japan and to Christianize these regions. Third, Spain wanted to participate in the spice trade that was monopolized by Portugal. Only the first objective was partially accomplished, because of the active resistance of both the Muslims in the south of Mindanao and the Igorot, the upland tribal peoples in the north of Luzon.

According to Gregorio F. Zaide, Spain had three major Gs for the Philippines: God (the preaching of God to the pagan Filipinos), gold (the accretion of the natural resources of the colonies), and glory (the glory that would come to Spain as the world’s colonizer).

The Arrival

It is still a bone of contention whether Magellan was the first European to reach the Philippines, because Tomé Pires (1512-1515) and other authors in Western Europe cited Luções (Luzon) before 1521. The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan reached the Philippines in 1521 while sailing for Spain in search of an alternate route to the East Indies. Spanish and Portuguese explorers landed on the island of “Limasawa” in the Philippines and claimed the islands for Spain and named them Islas de San Lazaro.

Magellan’s successful expedition, was followed by the fifth voyage under Miguel Lopez de Legazpi which was also a success. de Legazpi was designated as the islands’ first governor general in 1564. He erected the first permanent Spanish settlement and made Manila the archipelago’s capital in 1571. In the same year, he changed the country’s name from Islas de San Lazaro to Las Islas Filipinas in honor of the Spanish king, Philip II

To rectify an important segment of Philippine history, Teodoro F. Agoncillo wrote, “There are misconceptions in the treatment of our history that should be exposed and corrected for the intellectual health of our students and general readers. Foremost among them is the belief, so current even today, that Magellan discovered the Philippines.”

Without denying the fact that Magellan reached the Philippines, yet Agoncillo believes it was not the Spaniards who discovered the islands. To over emphasize Spain’s expansionism, its country’s writers blew out of proportion its might.

This is natural and should not be counted against Spain or Spaniards, for indeed Spain was great and wealthy at the time Magellan reached the Philippines. The statement, however, becomes funny when Filipinos repeat such obvious prevarication of truth, for our country already had commercial relations with her Asian neighbors hundreds of years before Magellan was born.

Nick Joaquin in his 1980 paper delivered before the Cebuanos talked about the years after the Magellan men left and before the next Spanish expedition came under Miguel Lopez de Legazpi – all 44 unaccounted years. After Magellan was killed by Lapu-Lapu in the Battle of Mactan, not much was heard about the image, except that the Cebuanos worshipped it as a rain god. Joaquin said that “during that strange interlude… the wondrous miracle happened: we accepted the Santo Niño as part of our land, part of our culture, part of our history. During those 44 years when the Cross had vanished from our land, the Sto. Niño kept us faithful to him”. It is such a symbol of Philippine history “because it came with Magellan, became a native pagan idol, was reestablished as a Christian icon by Legazpi, and has become so Filipino that native legends annul its European origin by declaring it to have arisen in this land and to have been of this land since time immemorial. Thus, the unaccounted 44 years of the stay of the Image in the hands of the natives is part of Philippine history. The Sto. Niño, as writer Joaquin put it, “connected, he linked, he joined together our pagan and our Christian culture; he belonging to both.”

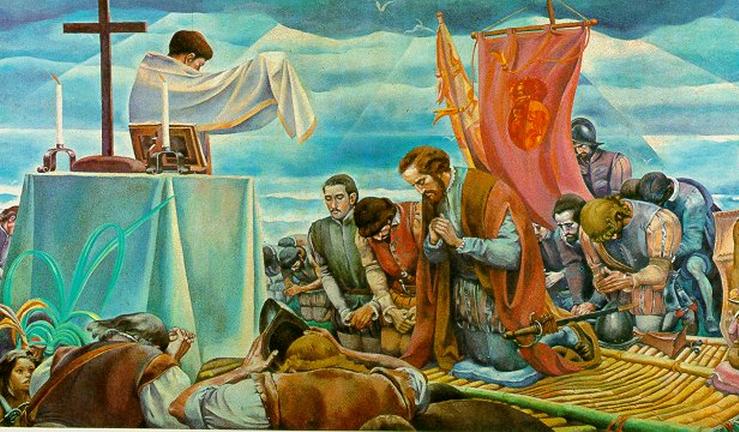

The First Missionaries

The very first friars who came with De Legazpi were the Augustinians. Later on, they were joined by other Spanish religious orders. It is said that the real conquerors were the missionaries, who armed only with virtues, won the good will of the natives.

In each friar in the Philippines the King had a captain general and a whole army. The French historian Par J. Mallat also made a similar observation. He said: ‘It is only by the influence of religion that Philippines was conquered. Only this influence could keep these (islands).’

The five religious orders that arrived in the Philippines to spread the Catholic faith were the Augustinians (1565), the first religious order that arrived and had the entire archipelago as their mission territory. These missionaries came with Fray Andres de Urdaneta. Four religious orders came later: the Discalced Franciscans (1578), the Jesuits (1581), the Dominican friars (1587), and the Augustinian Recollects (1606). All five religious orders had agreed among themselves to divide the entire archipelago for an adroit Christianization.

The Augustinians were given charge of the Tagalog provinces, Pampanga, Ilocos, Cebu, and Panay. The Franciscans took the Tagalog regions, Camarines, and the rest of Bicolandia. The Jesuits concentrated their efforts on Rizal, Cavite, Laguna and much smaller areas of Cagayan, and Pangasinan as well as Samar and Leyte. The Dominicans worked in Cagayan, parts of Pangasinan, and Bataan, Isabela, Babuyanes, Batanes, and the Parian, a ghetto outside the pueblo of Manila, where non-Christian Chinese lived. The Augustinians and Jesuits first had the Visayan Islands, but later on the Recollects joined them. The Augustinian Recollects got the outlying conquered territories of Zambales, Palawan, Calamianes, and the Jesuits had certain parts of Mindanao. Manila and the Port of Cavite were considered free zones

For easier pedagogy, each order was obliged to speak not more than four specific native languages. The missionaries did not only serve as vital links between the civil government and the natives and preach the Catholic faith in the specific native tongue, but also wrote books and dictionaries in the Philippine dialects. But it was not all rosy as far as evangelization of the natives was concerned. There were noticeable setbacks, because primarily Christianity was a few instances “forced” upon the natives.

The legacy of the deformed life the colonizers bequeathed to the Philippines could be expressed in what Carol Gilligan wrote in her book, In a Different Voice. She made a critique of the patriarchy and hierarchy which characterize the power structures of most of the world up to the present. In that patriarchal and hierarchical system, somebody invariably had power over somebody else and life was not as just to the person on the bottom of the pyramid as it was to the person on top of it. For instance,

“in terms of power and privilege, the men were over the women, the rich were over the poor, the healthy were over the sick, the historically privileged were over those with less historical privilege, those with white skin were over those with colored skin, those without physical handicaps were over those with physical handicaps, and humanity itself was over nature. In effect, someone was always over somebody else.”

Achievements

Unification through colonialization and Christianization of the archipelago was facilitated through the continuance of the native’s political structure, the barangay. The friars needed the local leaders who had the power over the small communities. Even though a centralized form of government was already in place with the governor general and the alcaldes mayores as heads of the provinces, yet the remaining authorities of the local government in the municipalities were natives.

The role of municipal mayor (gobernadorcillo), capitanes de barrio and cabeza de barangay was awarded to the elite class (principalia). The principales consequently became the links (fiscales) between the Church and the people. The pueblos did unify the scattered indigenous villages. At the same time, it provided colonizers and missionaries the instruments to strictly enforce upon the natives their laws and monitor their movements for possible incendiary activities as well as forbidden pagan practices.

The propensity of the church to pageantry gained wide following among the ancient natives. Celebration of fiestas, processions, dances, theatrical shows and Moro-Moro plays enhanced the assimilation of indigenous social customs into religious observances. They suited well the Filipinos’ manner for showmanship (“maporma”) as spiritual articulations of their relationship with the divinity. The Spanish pageantry helped the Filipinos novel forms of celebrating life’s milestones, such as weddings and baptism, yet the natives paid more attention to glitters and the externals, not to the real reason for the celebration. All the holiday glitter out there is more fun without any substance. “All that glitters is not gold.”

The Sword and the Cross

Abusive colonial rule

The colonizers did not only bring “lights” in terms of progress to the Philippines, but also “shadows,” in term of deformation of its cultural heritage, beliefs, and local practices. The Spanish clergy was very destructive of local religious practices because these were considered pagan. They systematically destroyed all indigenous holy sites and all representations of animist gods or goddesses. Since most of the pre-Spanish documents were considered pagan, they were also destroyed, thus, leaving only a handful manuscripts to historians.

The legacy of Spanish conquest and colonial rule as with other colonial power that dominated indigenous populations has manifold results. Once the indigenous Filipinos were under the dominance of the mightier Spaniards, they, though adamant, acquiesced to the colonizers’ demands. New moral laws were imposed on Filipinos and discouraged slave holding, polygamy, gambling, and alcohol consumption that were a natural part of the indigenous social and religious practices.

The Spanish missionaries shaped the Filipino spirituality. Much of the native pre-Christian cultural expressions survived in the process. In the end, the resultant spirituality is a syncretic blend of Hispanic imposition of Christianity mingled with superstitions and pagan practices.

Unfortunately, the way the indigenous culture was evangelized was not only destructive and oppressive, but also, as Jose De Mesa contends, “it was the harbinger of so many miseries and the cause of so much confusion, most especially among those colonized. Not only was it foreign to Asia, it was also an understanding which was polemical against non-Christian religions, disrespectful of indigenous cultures and insensitive to the injustices which colonialism brought about.”

Historians Rose R. Tope and Detch P. Nonan-Mercado believe that the friars came to the Philippines not to Christianize a people, but their animistic practices.

Fr. Cantalamessa remarks that the Catholic Church has a humongous set of doctrines and teachings. But these would not help at all an ordinary layman who has no relationship with Christ. This theological and sophisticated Catholic understanding and doctrines are taught indiscriminately to people. He said,

“We must follow a right order. All this comes later and will be very precious. But first we must put forth Jesus Christ. Be sure that people come to know Jesus-not necessarily all the theology about him. A living Jesus- not just doctrines or theories or books about Jesus Christ.”

Loss of racial dignity and ethnic pride

The cultural deformation of the natives wrought by colonialism and Christianization affected almost every aspect of the Filipinos lives, most especially their dignity and personal worth as a native Filipino. This colonial deformation is so embedded in the Filipinos psyche that it persists even today.

Filipinos were treated mercilessly and ruthlessly resulting into lessening their self-esteem and ethnic pride. They were caught in a hierarchy of superiority; the mestizos bowed to the “criollos” (offspring of Spanish parents), the “criollos” to the “peninsulares” (those with parents born in Spain), while the “Indios” or the Filipinos knelt before everyone. The recurring reminder of the Filipino weakness inculcated into the minds of the citizens that until today some Filipinos still feel inferior and uncomfortable around foreign races.

Loss of indigenous lands

Religious orders and church officials acquired great wealth, mostly through land grants. In later years, one of the reformers’ demands was the return to the Philippine landless farmers the properties the Spaniards had claimed as “friar estates”. Instead of devoting their time and energy for the progress of the colonized people, they were preoccupied with pastors’ needs more than the pastoral needs.

Filipinos held only minor offices and majority did not receive the benefits of public education and their rights and wishes were almost completely ignored. Laws promulgated for their protection were not enforced.

There was a power struggle between the religious and civil Spaniards for financial profit of the islands’ resources and even for political supremacy over the archipelago between the governor-general as civil head and the archbishop. During this squabble, the native Filipino were neither privy nor were they given the right how to rule the archipelago! In the late 17th and 18th centuries, the archbishop, who also had the legal status of lieutenant governor, won the political control. Augmenting their political power, religious orders, Roman Catholic hospitals and schools were built, and bishops acquired great wealth, mostly in land.

The Spanish monarchy bestowed on the colonizers grants that comprised the core of their holdings, but many arbitrary extensions were made beyond the boundaries of the original grants.

Other abuses

Abuses of civil and ecclesiastical authorities became widespread: moral decadence, brutality of the Spaniards against the inhabitants, especially those who disregarded the Roman Catholic tenets of faith, religious orders’ violations of the vow of chastity. These abuses became one of the reasons for the birth of the propaganda movement:

the “La Solidaridad” (1892) by Marcelo H. del Pillar in Barcelona, the “Associacion Hispano-Filipina” (1892) by Mariano Ponce, the “Liga Filipina” (1892) by Dr. Jose P. Rizal and the “Kataastasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan” (KKK or Supreme Society of the Sons of the Nation), and most especially the writing of “Noli me Tangere” (1886) and its sequel “El Filibusterismo” published in Ghent by Rizal. The two books opened the eyes of the Filipinos that eventually paved the way for major and minor revolutions.

The union

The cross as well as the sword held sway over the archipelago. They were so united in implementing their goals that it became impossible to dissociate one from the other. A critique of the Spanish abuses did not spare the church. In exposing the injustices and oppression heaped upon the indigenous Filipinos by the Spanish government, for example, Rizal was brazen faced in his denunciation too of Spanish clerics’ abuses.

The problem of the relations between government and religious organizations in the Philippines is of a peculiar type. For several hundred years the Roman Catholic Church and the state have been so closely intertwined in the islands as to be inseparable to the eye of the ordinary man. The church question has been above all things a question of politics. Religion and politics were synonymous. Little can be said of administration under the Spanish régime without connection with religion or anything in the church was always in reference to its political functions.

Christianization: Hispanic sentimentality on suffering and death.

In general,Filipinos are a sentimental people. Emotions play a major role in their life. They normally decide with their heart more than their mind. Consider how the soap operas or teleserye attract so many viewers not only in the Philippines, but also in foreign countries where Filipinos reside.

For this reason, suffering and death appeal to many Filipinos. Holy week observance, especially Good Friday, is very popular. Some theories say that the early Filipinos’ veneration of the dead is a product of post- Spanish popular faith that is marked by sympathetic obsession with death and a religious fervor that focuses on the wounds and sufferings of Christ. The Christ image that is widely admired by ordinary Filipinos portrays Jesus as suffering, humiliated, and sacrificed.

Spanish Catholicism has been characterized by a deep sense of tragedy, a morbid obsession with death, and religious contemplation of the wounds and death of Christ.

A spirituality that overemphasizes suffering and death over struggle and victory can easily fall into superstitions and magical rites. Dying and death, similar to other milestones in Philippine life, such as marriage and birth, are shrouded in superstition and magic. The Filipinos’ morbid fascination with death conjoined with superstitious beliefs is seen clearly on Good Friday. Herbs left at the foot of the Crucified Christ are picked up after the “Siete Palabras” (Seven Last Words) by the faithful who believe that they are sure remedies for all kinds of sickness. A few uneducated Filipinos still believe that amulets could be possessed on Good Friday.

In fairness and justice to Catholic missionaries of colonial era, there is no doubt they also preached to the indigenous Filipinos the love of God emanating from the Trinity. But it was overshadowed by overemphasis on other Christological tenets, such as atonement, suffering, and sacrifice that they believed the early Filipinos needed most.

Sister Mary John Mananzan, OSB, observes that Spanish religiosity and its Mexican adaptation decisively affect the Philippine Christ figure. The traditional Spanish Christ is rather docetic. (Docetism (Gk. dokesis, appearance or semblance is an ancient heresy that denies Christ’s human nature.) Christ has little connection or relevance to the here and now, struggles and frustrations, dreams and aspirations of the Filipino people. It is a Christ that leaps from the crib as an infant Christ to the Christ on the grave.

“While Good Friday was dramatized, there was no concomitant celebration of Easter, the beginning of new life. By emphasizing the mortal suffering of a beaten, scourged and defeated Christ as well as a spiritualized salvation in the other world, the Christian message was used to legitimize the colonial order by pacifying the people.” The intention of the Spanish friars was noble, but they imported the European version of Christianity without adapting it indigenously to the Philippine culture. Most of the religious practices and rituals were observed by Filipinos in Hispanized version. The missionaries had religious and liturgical practices as they did in Spain and introduced them in the Philippines.