by Abraham dela Torre

IF YOU DIDN’T know him, you’d never believe Rev. Fr. Roberto Laad is a priest. His height is below that of the average Filipino male which, to his advantage, makes him look like a school boy, what with his regular denim-and-t-shirt get-up and a backpack perpetually slung on his shoulders. His brown skin and short hair support his boyish mien and his agility only underscores it. Like me, he is a walker, and is constrained to take the taxi only when commissioned to say the 6 am Mass at the Holy Spirit Parish, wary of the punctuality of the parishioners there. Transparently humble and moderate in movement and speech, he touched me when, in one of his always moving homilies, he confessed to the congregation his even humbler origins. And thanked the people responsible for his transition from a petsay peddler to the priest that he now is.

That Thursday that he said Mass was the Feast of St. Raymond of Penafort, patron of (canon) lawyers. The Gospel was about the Spirit of the Lord being upon Him, anointing Him to bring good news to the poor, proclaim liberty to captives, give sight to the blind, free the oppressed and announce the Lord’s mercy.

In most of his homilies, Fr. Robert never fails to defer to God as love. Here is one homily of his that moved me deeply to pester him with a copy of the sermon that I may share it with the readers of this website.

He called it the Parable of the Good Palestinian. It was high noon in an obscure airport somewhere in the Middle East. Abraham Weinstein, an American tourist, was furious. He was told that his return flight to New York had been cancelled for security reasons. As he looked around helplessly, he saw two men in baggy trousers, ill-fitting jackets, and checkered keffiyah headdresses indicating they were Palestinians. Before he could make a move, one of the men fired two shots at him. Simultaneously, two other men opened fire at the ceiling. As the crowd scattered in panic, the assassins walked away casually.

As Abraham lay on the floor, people simply passed him by. Years of war seemed to have insulated them from a sense of compassion or concern. As the last conscious spasm shook his body, his senses floated into cold darkness.

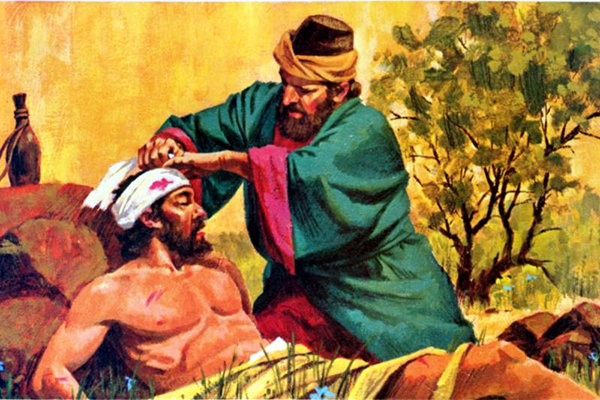

When Abraham opened his eyes, he was in a small room that was bare except for two oversized cabinets. On the small table beside his bed were a surgeon’s instruments in disarray. Someone had saved him. The door opened, and a very tall man entered. “I am Dr. Mahmoud Jamil, I saw what happened at the airport.” he said gently. He brought with him a bowl of simmering soup. “Thanks for helping me,” Abraham said, and added, “Are you a Jew like me?” Mahmoud replied, “I am a Palestinian,” Abraham panicked. Mahmoud smiled reassuringly. “Don’t be afraid. I am not one of those who shot you,” said Mahmoud.

As he fed Abraham, Mahmoud narrated this story: “Three months ago, I went home to find our house surprisingly quiet. When I passed by our parent’s room, I heard a loud snoring. I thought they were both asleep. The snoring suddenly stopped after an hour or so. Curious, I peeped inside; I was horrified. My parents and my younger brother were hanging upside down from their noses and ears. They must have been in that position for hours. The “snoring” I heard was their agonized moaning and gasping. They could not breathe; blood clogged their noses and throats. It was too late. I, a doctor, could not do anything to save them.”

Mahmoud continued: “Ever since I was born, I have never known what real peace is. Every day, I see a somber pageant of revenge, of moral atrocity. The world seems like one angry cesspool of terror. How can heaping one violent act after another be holy and just?” he looked at Abraham and said, “When my loved ones died, I vowed to take vengeance.”

Instinctively, Abraham looked at the surgeon’s knife at the table. It suddenly looked like an attractive instrument for bandaged wounds. “This is my vengeance, my friend. This is my protest against all the violence in the world. I destroy violence by healing the wounds it inflicts. This is the kind of vengeance that makes us, Muslims, witnesses of a God who shows mercy over our world despite its wickedness.”

Abraham listened. He looked at that pale, bearded face and those magnetic, piercing, black eyes. In the presence of the Palestinian named Mahmoud Jamil he, Abraham Weinstein, an American Jew and a theorist, felt humbled and worthless. Yes, he was in a small room that was bare except for two oversized cabinets. And at the mercy of a foreigner who, if not for an avowed pledge to counter violence with kindness, would have easily done him in.

The Thursday after that, his homily was about the leper whom Jesus not only willed healed but also physically touched, a whole world of difference from His usual miracle works, where He merely used words. Fr. Robert described leprosy as an ordinary bruise, itch, scratch or wound that becomes an abominable skin disorder to the so-called clean because of their self-righteous perception that they are a cut above the rest. They are the ones that isolate the diseased, label them unclean and cast them out of their holy society. But Jesus disproved their condemnation through curing the leper by touching him, an act which is an abomination itself, to the horrified spectators. Because the leper, resigned to his empty existence, saw hope in Christ, and pronounced from his heart of hearts the will of the Healer as his ultimate cure. Jesus, forever merciful and compassionate, saw and heard and felt him. And returned his faith with a seeing, hearing, giving, forgiving, healing, loving touch.

Fr. Robert’s homilies touch because they interrelate and relate to his humble origins. Are not the poor and marginalized almost on the same level as the sick and the wounded? Treated by some with a ten-foot pole sympathy and shunned by many as outcasts of society.

How many Mahmouds are there in this era where Pope Francis advocates mercy and compassion? How many lepers will be touched by even a look of pity? How many self-righteous churchgoers will judge a priest by the former’s perceived sacrilege of the latter? How many privileged donors will have the cheek to proclaim their precious contribution to the church coffers by affixing it to one of the Trinity?

Ahhh, to imagine the poverty of a petsay peddler whose dogged determination to build boys into men of the cloth compel him to beg for sponsorships. And get the reward in gumption poking at his face of his unworthiness. Yet he is undaunted. Only thankful of perhaps his just desserts. A mite compared to the passion and death of Christ.